Innovation Spotlight

Innovation Spotlight: Virtual Design Construction and Adam Miller

Flatiron is embracing an Innovation Mindset by incorporating Virtual Design and Construction (VDC) techniques into our work at Denver International Airport. Leading the way is Adam Miller, VDC Engineer, at the DEN Concourse Expansion project.

Adam sometimes calls what he does “triple constraint untangling.” By tapping the capabilities of a 3D laser scanner and sophisticated software systems, he develops high-density spatial images that accurately show an as-built construction project. Together with 3D models developed by the trade partners, these pre- and post-installation models facilitate clash detection and resolution involving scope, cost and time.

Adam joined Flatiron in 2011, shortly after graduating from the University of British Columbia with a degree in Civil Engineering. His first assignment

was as a field engineer on the Donald Bridge project in Golden, British Columbia. After picking up some project skills in areas such as surveying and quality control, Adam moved to the Design Engineering team in Denver. In that role, he had the opportunity to design overhang formwork for bridges and bridge crawler gantry sequences. Following a stint as a project engineer in the Denver metro area—focusing on bridges, spillways, underpasses and runways—Adam joined the Denver airport team.

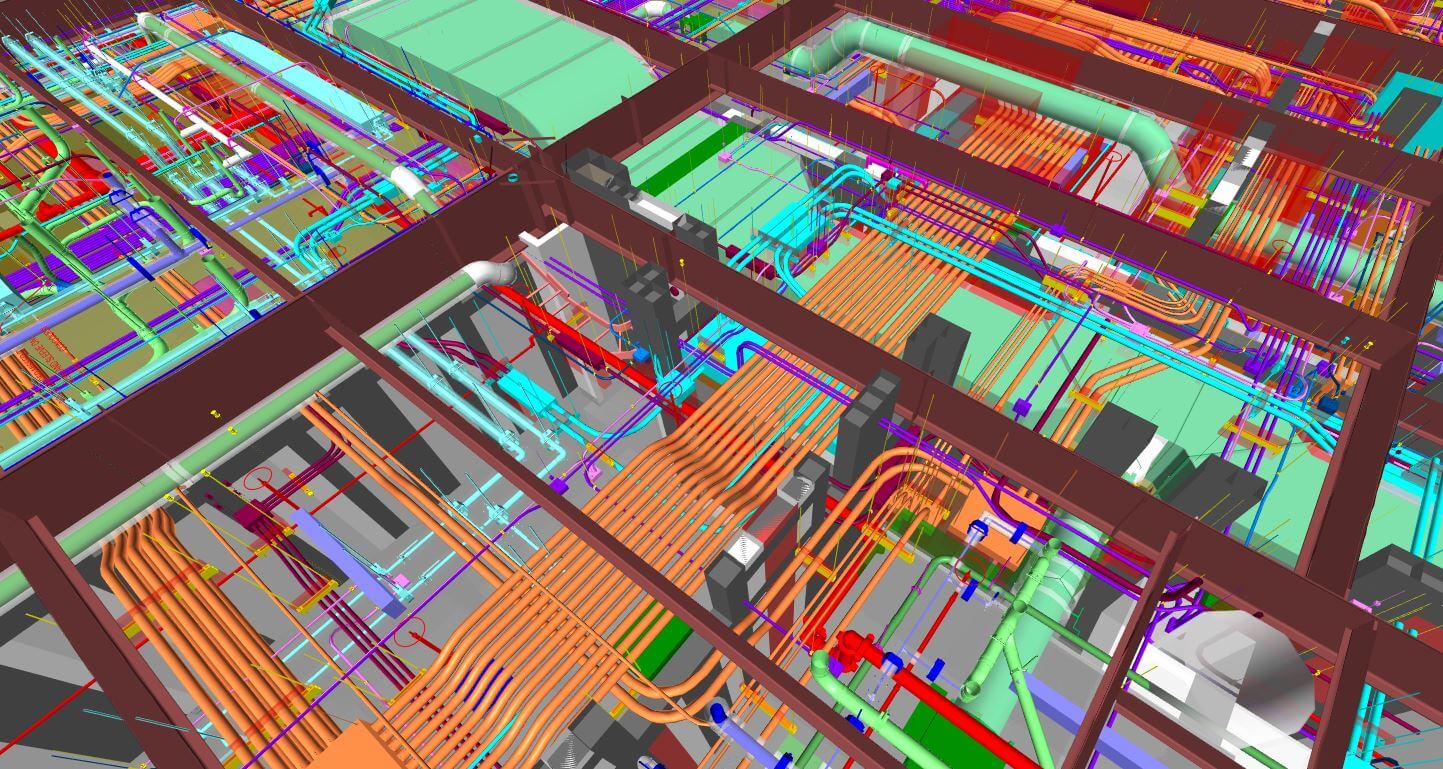

For the Concourse Expansion Project at Denver International Airport, Adam brings his laser scanner to the project site regularly to scan work that’s in progress and that’s been done since his last scan. By uploading this information into his computer system, he is able to “stitch together” a three-dimensional visual model of the current state of the project. Adam and project colleagues are then better able to determine actual or potential issues.

Perhaps an on-site condition had necessitated installing piping at a slightly different elevation than called for in the construction plans. This reality will be shown in the as-built visual model. And it enables the team to make any necessary modifications in plans for the placement of other piping or systems running in the same location.

Greater collaboration and communication are inherent in the process as the construction team can focus on a single model that brings together

several subsystems that may have been designed separately. Members of the team can identify potential construction conflicts before they result in reworks and project delays.

“Elimination of rework comes from optimizing space to help get installation right the first time,” Adam says. “All trades want to lay out their work as efficiently as possible to minimize material, but two objects cannot occupy the same space—and that can create a ‘clash.’ We try to catch these clashes and sort out ‘who needs to move where’ to clear it up.”

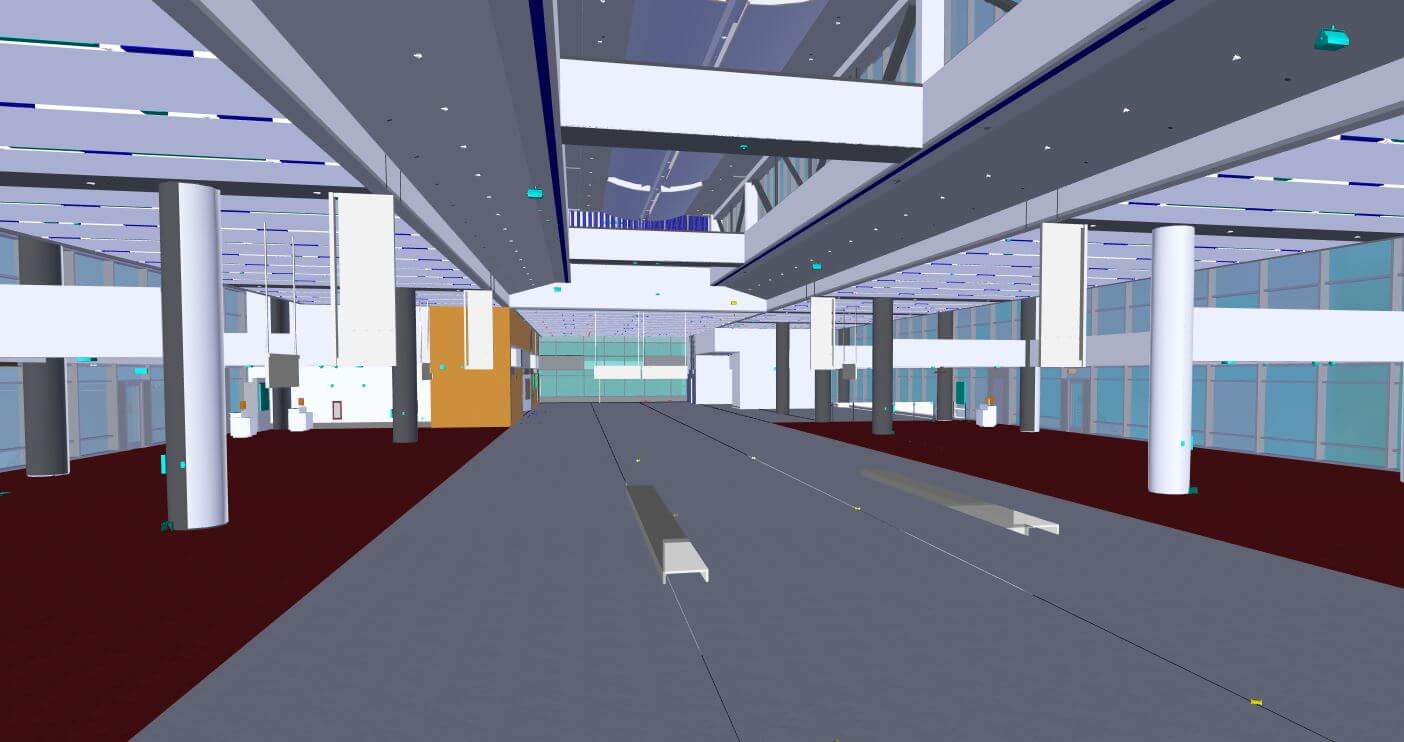

At the end of the project, the three-dimensional visual model is one of the final project deliverables for the project owner. While as-built drawings or diagrams are typical among final project deliverables, the VDC model is much more holistic. Further, it’s a valuable tool for maintenance and repairs as well as potential future building modifications.

The backbone for Virtual Design and Construction (VDC) is Building Information Modeling (BIM), which combines as many of the project scopes as practicable into a 3D representation of the overall project. This enables project engineers and project contractors to see how everything fits together, how to untangle conflicting systems, how to optimize utility routes, and what structural and architectural designs are needed.

This is particularly crucial for mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems for a project—as these systems often must fit into dense spaces above ceilings and between walls.

According to Adam, “More often than not, small systems, accessories and access requirements take up more space than originally assumed, making free-space especially rare. Placement tolerances in the model generated via BIM and installation tolerances in the field are also often different. A significant benefit of the laser scanner is to determine whether anything installed in the field differs from its intended location in the model, and to determine the severity of that difference. Can it can be left in place (and the model updated), or does it now conflict with any current or future work (requiring a new solution to be determined).”

Adam notes that “VDC is an entire lifecycle process. It provides value to the trades at the outset by eliminating as much rework down the road as possible. Further, it provides value to project owners by creating a resource they can depend on as an accurate representation of their assets—product model, location, expected life, maintenance resources, record of inspections—all the way through the life of those assets.”

So what brought Adam into this realm?

He says that in high school, he first became interested in what computers could do to influence construction. He immersed himself in related electives and followed up with a university course typically reserved for students seeking masters’ degrees. In that course, his team won the class award for its final project. His interest was further stoked on the Donald Bridge project where field engineers were able to do most of the project surveying. This allowed him to program precise intersection grading and the like into GPS equipment. And he recalls volunteering whenever he became aware of any potential opportunity to be associated with advanced systems like VDC.

“I realized recently that what I do each day is very similar to a nonogram—a logic-based spatial puzzle,” Adam says. “And spatial puzzles happen to be a favorite pastime of mine. So I’m glad to be doing what I’m doing.”