Project News

Parsons Creek: Flatiron Construction Crews Uncover 100-Million-Year-Old Fossil

In late December, Flatiron, a major contractor in Fort McMurray, completed the Parsons Creek Interchange Geotechnical Improvements for Alberta Transportation. The project involved the excavation and embankment of common material to improve ground conditions at the site of a future interchange on Highway 63, three kilometers north of Fort McMurray, Alberta. Working 24-hour shifts during the three month project, crews stripped the footprint of the interchange, removing the native muskeg, which was up to three meters deep in places. Crews then transported dirt from one side of the highway to the other, filling to a design elevation and installing vertical wick drains. In all, crews moved just over 1.1 million cubic meters of dirt.

In early November, excavation work uncovered an amazing discovery: a nearly complete 100-million-year-old fossil of a large, extinct marine reptile—a plesiosaur. Principal paleontologist Michael Riley of Aeon Paleontological Consulting first discovered the fossil on a cold morning on the project site.

“We were tasked with following behind each pass of the earth scrapers searching for fossils. I was surveying the excavation when I noticed a small fragment of bone material.”

That small fragment turned out to be a big find. In the painstaking excavation that took place over the next month, Michael and paleontologist Kevin Aulenback uncovered a nearly-intact fossil of what is likely a long-necked plesiosaur.

“When you think of plesiosaurs, think of the Loch Ness Monster. They have four flippers, a broad body, a short tail and a long neck,” said Michael.

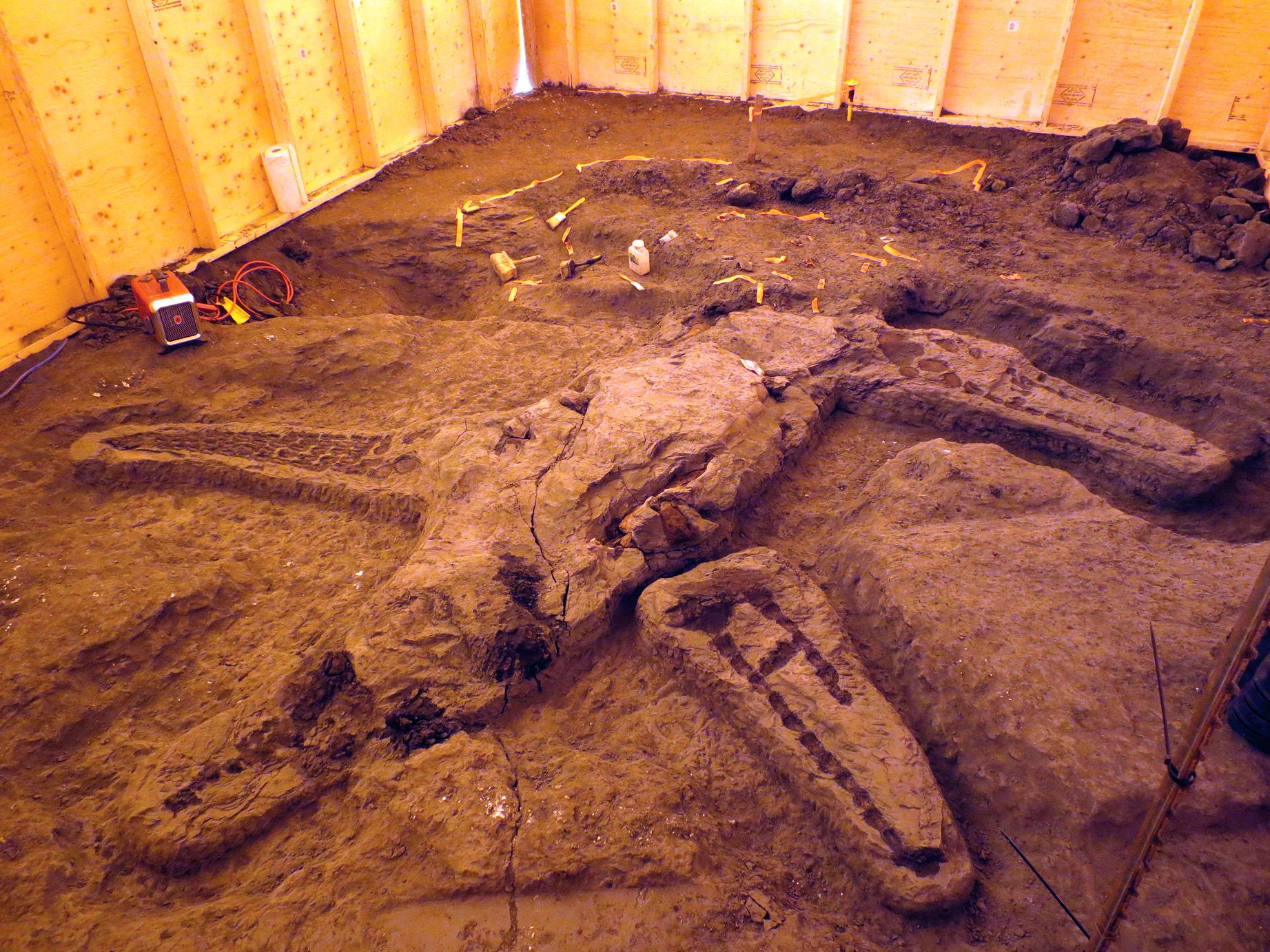

Plesiosaurs can reach up to 14 meters (nearly 46 feet) long. This fossil measures approximately half a meter wide with flippers extending about one meter to each side, and Michael estimates the length of the body is at least five meters long.

Flatiron crews built a small insulated shelter around the excavation site as winter temperatures dropped—the temperature with wind-chill was minus 40 degrees Celsius (-40 degrees Fahrenheit) during portions of the excavation.

“All of the Flatiron guys on-site were super helpful and cooperative,” said Michael. “I was really impressed at how smoothly the entire operation went.”

Approximately 110 to 114 million years ago, plesiosaurs lived in the ancient sea that covered most of Alberta during the early Cretaceous Period. What remains of the seabed is now called the Clearwater Formation. The fossil was found in the Wabiskaw Member, a layer of this formation that is known to be rich in marine vertebrate fossils. Paleontologists also recovered thousands of other fossils including fish bone, ammonites, scallops, mussels, clams, snails and large pieces of fossilized wood, among other finds. The plesiosaur, however, is by far the most exciting discovery.

Approximately 110 to 114 million years ago, plesiosaurs lived in the ancient sea that covered most of Alberta during the early Cretaceous Period. What remains of the seabed is now called the Clearwater Formation. The fossil was found in the Wabiskaw Member, a layer of this formation that is known to be rich in marine vertebrate fossils. Paleontologists also recovered thousands of other fossils including fish bone, ammonites, scallops, mussels, clams, snails and large pieces of fossilized wood, among other finds. The plesiosaur, however, is by far the most exciting discovery.

The energy-rich oil sands in Fort McMurray sit just below the Wabiskaw Member, and excavation there has turned up similar fossils. This specimen is one of the first to be discovered outside the oil sands operations in this area and is extremely well-preserved, missing only the skull and one flipper.

“It is the most complete specimen of this type of plesiosaur recovered from this formation to date,” said Michael.

Over several weeks, the paleontological team worked through the cold weather to carefully uncover the fossil. The find was right in the middle of the project site and crews continued excavation around the structure.

“They kept digging, excavating about ten meters below the fossil site,” said Michael. “We were on an island.”

Once excavation was complete, the fossil was encased in fiberglass plaster and sent to the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta, where it will undergo further analysis.

Meanwhile, Flatiron crews wrapped up the Parsons Creek project, which also included the realignment of a creek and the establishment of a Stormwater Management Facility. Although construction is now complete, analysis of the skeleton is ongoing. It will likely take several years before researchers release a full report on the find.

“It’s a pretty cool thing to have happen on your project,” said Flatiron project manager Stephen Hickey. “It was a bit inconvenient for the work, but exciting for the team.”